Caring Work and where to find it: concerns mechanism

Published by Manuel Rivero on 30/11/2022

Caring work.

In our previous post about caring work we described how the concept of caring work[1] had been very useful for us in the coaching work we did with several teams during all of 2019 and a big part of 2020.

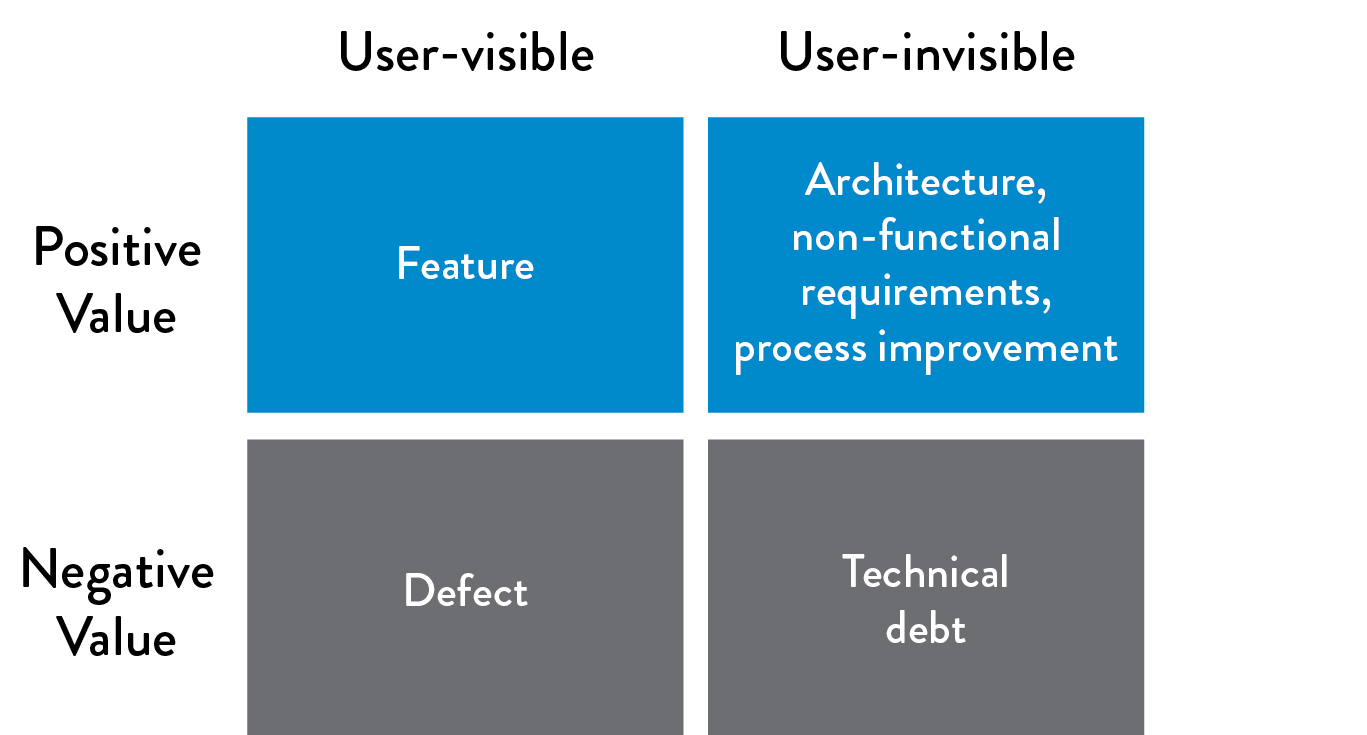

We used the concept of caring work to redefine the very concept of value in our client, so that producing features as quickly as possible (productive work) was not the only type of work considered valuable, and they started to also see value in work concerned with keeping the health of the ecosystem composed of the code, the team and the client (caring work), so that it can continue evolving, being habitable for the team and producing more value for its users. They understood that aside from productive work, we also needed to devote energy and time to caring work.

How did we apply the concept of caring work?

The way to apply caring work in a team highly depends on the team’s context. Do not take this as “a recipe for applying caring work” or “the way to apply caring work”.

In this post we mostly talk about our experience working with Lifull Connect’s Barcelona B2B team which was the first team we worked with inside Lifull Connect. We later introduced small local variations to adapt these ideas and mechanisms to the context of other Lifull Connect’s teams, and to their coaches.

We took two main decisions[2]:

-

To protect a given percentage of time/effort in every iteration for caring work. The specific distribution of time/effort between the two types of work depended on the context of each of the teams we worked with[3].

-

Only developers could decide which caring work was needed.

How did we identify caring work?

"A process cannot be understood by stopping it. Understanding must move with the flow of the process, must join it and flow with it." — Frank Herbert

A complex system is in constant flux, and any action may change the system in unpredictable ways. So after any change[4] we need to observe the new dynamics that start to form and apply suitable corrections. But, how could we sense the dynamics of the system in order to adapt to it?

We decided to use a concerns mechanism to detect system health problems and try to solve them as we went.

The concerns mechanism.

A concern might be anything someone working on the system doesn’t understand, doesn’t agree with, thinks that might be problematic, or thinks that might be changed to improve the system’s sustainability. The concept of a concern[5] was described by Xavi Gost in his talk Consensus-driven development (CDD)[6].

Consensus-driven development is based on the premise that developing software is a team endeavour, and on seeing the current system as an implicit representation of the real team’s consensus about what they are currently developing. This consensus will evolve to adapt to contextual changes. Not acknowledging this tacit consensus may cause problems in the team’s dynamics.

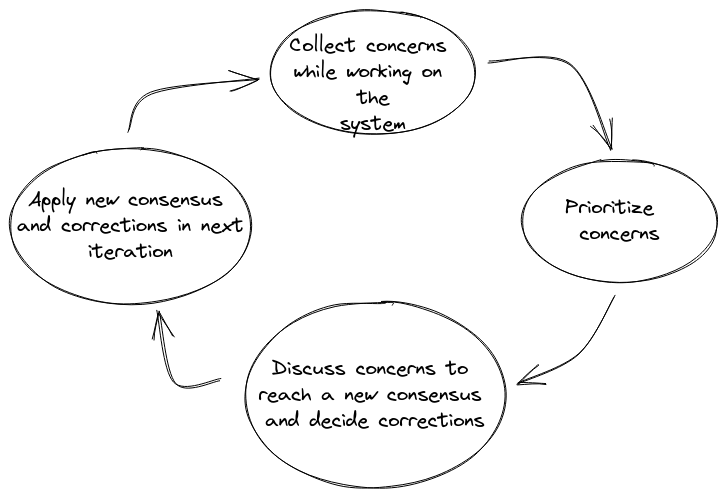

The concerns mechanism we used follows the process indicated in the next figure:

This mechanism gives the team a way to raise concerns about the current team’s consensus so they can be discussed. It also helps to make the actual team’s consensus about the system explicit.

We find the concerns mechanism very interesting because it:

- Fosters technical conversations.

- Serves as a space to manage conflicts and reach new agreements that make the current team’s consensus explicit.

- Helps to transmit knowledge.

- Detects waste in the part of the software value stream comprising development to delivery.

We had found a way to sense the dynamics of the system.

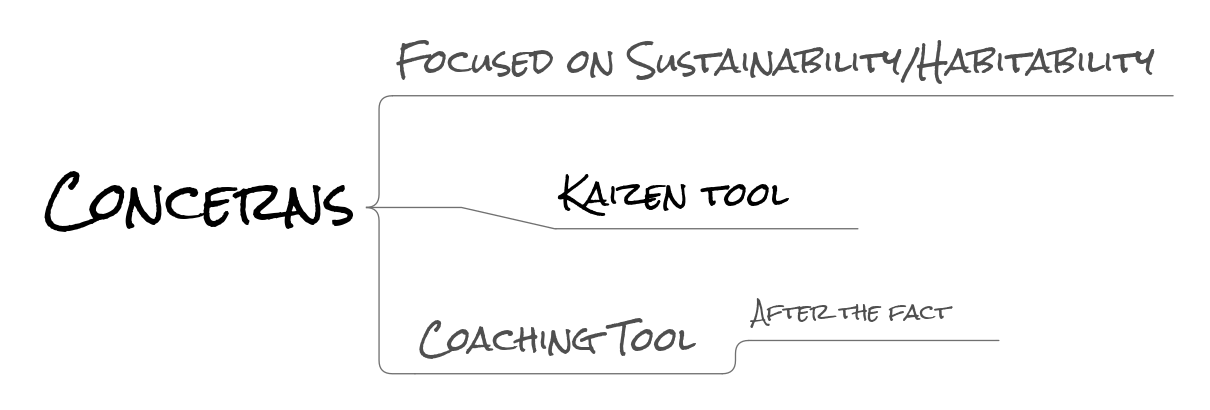

The concerns mechanism is a kaizen process enriched with information from the people actually involved in the actual work. It helps to apply several Lean Software Development principles, such as, Eliminate waste, Amplify Learning and Empower the team.

Our goal was not only to improve the developers’ experience by creating an environment, practices, architecture and infrastructure in which the team members could learn and work better and with less stress[7], we also wanted to develop the team’s technical skills.

The concerns mechanism can be a great coaching tool. Since the technical coaches were outnumbered by the team members[8], the concerns mechanism provided us a space to solve team members’ doubts and raise our own concerns about design decisions. This made it an additional after-the-fact coaching tool, which complemented other live coaching activities, such as, the ensemble and pair programming sessions we had with the team.

In this coaching context, the discussion of concerns made more emphasis on learning than on reaching consensus, especially at the beginning of our work with the team. Later, as the team was more mature, the emphasis changed. The idea was that once we leave, the team could keep on using the concerns mechanism on their own to reach consensus and detect caring work.

Concerns collection and prioritisation.

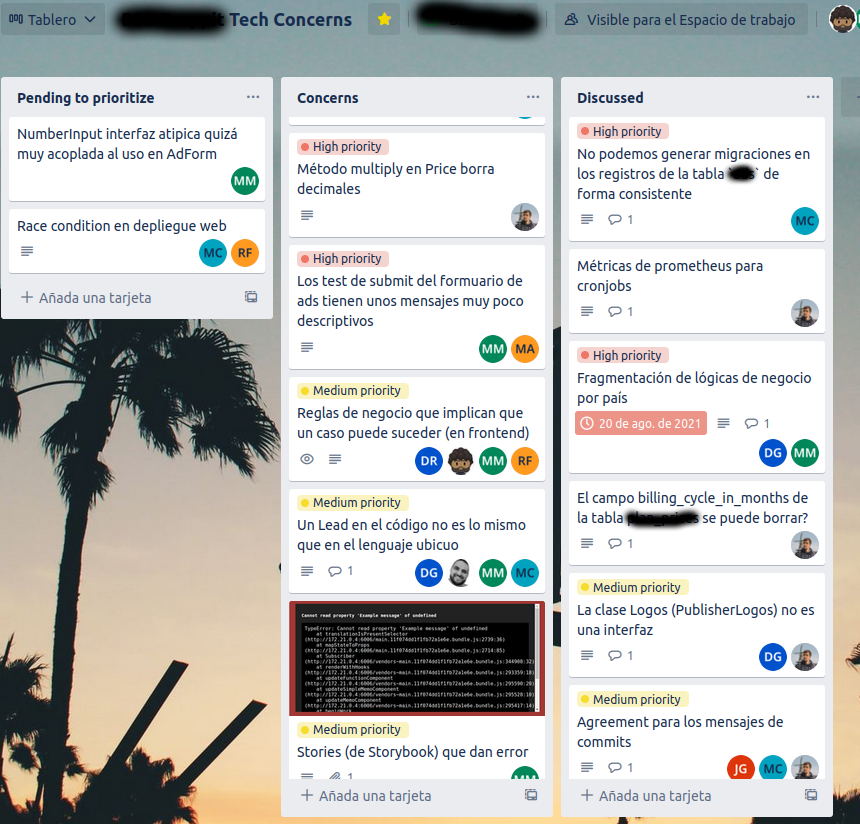

During an iteration, the team raised concerns by describing each of them in cards that were added to a separate board dedicated to this purpose. Below you can see the concerns board of one the teams:

At the end of the iteration, we had a fifteen-to-thirty-minutes meeting in which we prioritised the new concerns on the Pending to prioritize column. We used three possible levels of priority: high, medium or low[9].

To prioritise a concern, after a brief explanation of the concern followed by some questions to clarify possible doubts, the team members responded in parallel to the question of “how important do you think discussing this particular concern is?”.

A variant of the planning poker dynamics with only three cards with values 1, 2 or 3, which corresponded to low, medium and high priority, respectively[10] helped us reach consensus about the priority. We used PlanITPoker but any similar tool will do.

Concerns discussion and outcomes.

Once a week we held a one-hour meeting to discuss the concerns with higher priority. For each concern card, the team members that had raised it, explained further the concern’s description, and answered any doubts that the rest of the team might have about the concern. Sometimes, other team members provided information about similar problems they had observed in other parts of the system.

After understanding the concern better, we discussed it for a while to try to determine its possible causes and effects, then, we proposed and discussed possible ways of solving or, at least, mitigating the concern. In these discussions, we tried to reach consensus and good enough/pragmatic ways to address each concern. In order to foster the team’s sense of agency and autonomy, we focused on what it could control and change at any given moment. However, sometimes, this was not enough and we had to escalate the concerns to higher levels, with the intention of somehow modifying organisational constraints or policies that were affecting the team.

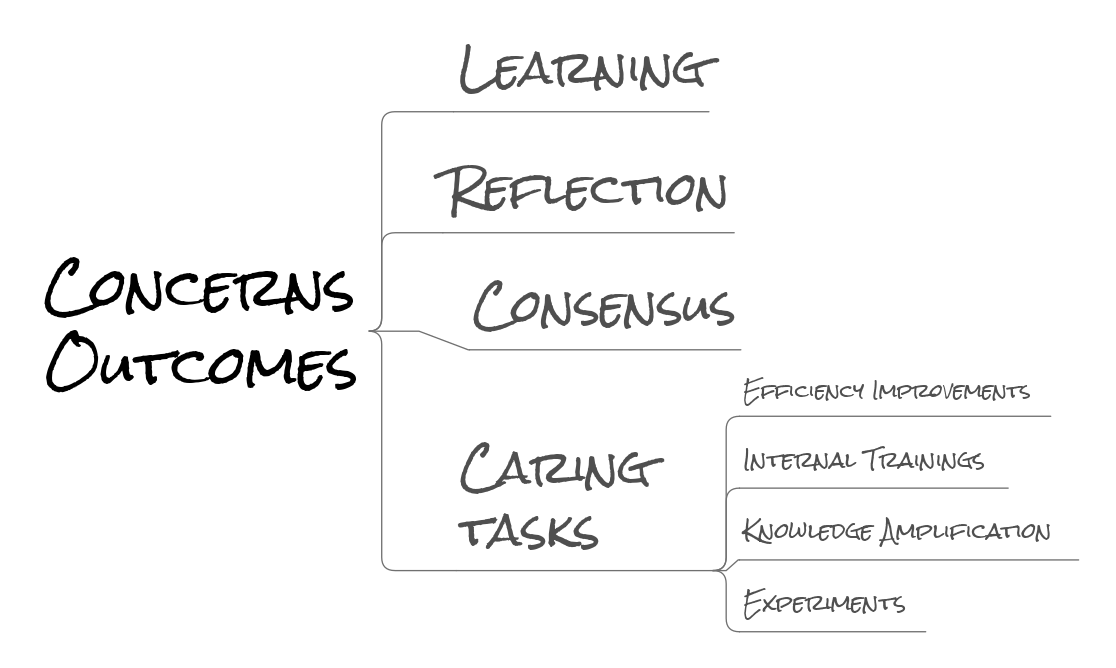

Depending on the specific concern, the team obtained different outcomes from its discussion (often several of them at the same time):

a. Learning about new concepts (code smells, antipatterns, design principles, patterns, techniques, tools, etc). Sometimes, the coaches helped the team, and other times the team members taught each other.

b. Reflecting on the current consensus of the team, thus, making it more explicit and transmitting it to everyone.

c. Evolving the current consensus of the team by getting to new agreements or revising old ones.

d. Detecting caring work to be done. The detected caring work was recorded and described in caring tasks cards that we collected in a different board. The caring tasks might be very varied depending on the nature of concerns that originated them. Some consisted of research in the form of experiments[11], others resulted in internal trainings, and others were efficiency improvements of any kind (paying technical debt in code, infrastructure or architecture, writing documentation, improving the ubiquitous language, etc). Anything that we needed to keep our system healthy.

In the following figure we show an example of the modification of a previously existing agreement after discussing a concern.

Notice how we recorded the new agreement as a comment in the Trello card. We think that it might be more useful to document these agreements that make the consensus explicit in Consensus Records, (CRs) that might follow a format similar to the Architectural Decision Records, (ADRs).

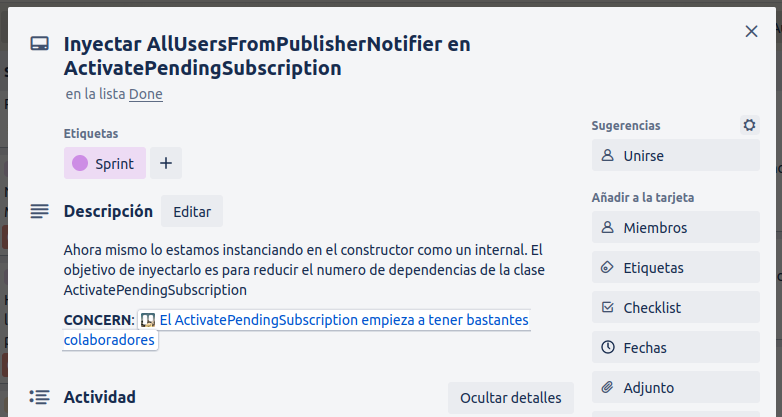

The following figure shows a caring task produced after discussing a concern about an action that had accumulated too many collaborators, and recorded how the team had decided that they could reduce the number of collaborations and remove some duplication:

Why did we decide to discuss concerns in a dedicated meeting instead of using the retrospective?

Retrospectives are also a meeting that provides a space to reflect and learn, in order to improve the efficiency of a team. They ideally include all the people that might help finding better ways of delivering value (product, tech, ux…). Why not use them, then?

We’d like to start by stating that by no means the concerns meeting should substitute retrospectives. These meetings have different, though sometimes a bit overlapping, scopes. We think that they are both useful and should be complementary.

Still, there are reasons why we think that concerns should be discussed in a different meeting than the retrospective.

On one hand, there’s the matter of who can best contribute to the discussion and of not wasting people’s time in unnecessary meetings. As we described earlier, concerns are a way to detect waste in the part of the software value stream comprising development to delivery. This means that most concerns are technical in nature, so for most of the discussions there would be no point in having non technical people in the meeting as this would waste their time. We think that this is true, regardless of having or not a healthy dynamic between product and engineering.

On the other hand, we wanted to protect the team’s autonomy to decide which caring work to do because they are the ones that work with the system and know where the friction and inefficiencies are happening, and have better information to fix them. We think that this makes sense from the point of view of the lean principle of Empowering the team. Besides, the DevOps movement also defends that engineering should spend the time devoted to caring work as they see fit[12] (which for them amounts to at least 20% of the team’s time).

Besides, the cultural dynamic around the B2B team when we started working with them, was characterised by a strong power imbalance between the product and engineering teams which left the latter little autonomy and agency. In order to create a space safe from this vicious dynamic, we decided to discuss the concerns in a separate meeting in which only the members of the engineering team could participate. This strong boundary fostered the autonomy of the engineering team and made caring work possible[13].

Having said that, some concerns needed a different approach.

-

Concerns that went beyond what the engineering team could control and change, or that required knowledge that the members of the team didn’t have yet. In those cases, we either invited whoever could provide the needed information to the concerns meeting, or took the specific concern to the retrospective.

-

Concerns caused by blocks due to how the company organised the teams. These kinds of problems related to Conway’s Law are very hard to fix, and their symptoms can at best be mitigated within the team. We took those concerns to the retrospective as a first step to gather more information before escalating them.

Summary·

In this post we have explained how we applied the concept of caring work in several teams of Lifull Connect for more than a year. Remember that the application of this concept depends on the team’s context. Do not take this as “a recipe for applying caring work” or “the way to apply caring work”.

We, first, showed how we created a safe space for caring work by devoting a given percentage of time/effort to it in every iteration, and by giving autonomy and agency to developers to decide which caring work was needed.

Then we showed how we applied the concerns mechanism to identify caring work and improve consensus about the system and communication in the team. The concerns mechanism also proved to be a great after-the-fact coaching tool that complemented other live coaching tools we were using.

We also described how we collected, prioritised and discussed concerns each iteration, and talked about the different outcomes we got from discussing concerns.

Finally, we gave our reasons for using a separate meeting to discuss concerns instead of using the retrospective.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lifull Connect’s Barcelona B2B team, for all the effort and great work they did to make the concerns mechanism work for them. That great work made it much easier for other teams in Lifull Connect to start applying the idea of caring work with the help of other Codesai coaches.

Also thanks to my Codesai colleagues, Antonio de la Torre, Rubén Díaz, Dani Ojeda and Fran Reyes, for giving me feedback about several drafts of this post.

Finally I’d also like to thank Karolina Grabowska for her photo.

Notes

[1] Idea from economic studies from a gender perspective where caring work is defined as “those occupations that provide services that help people develop their capabilities, or the ability to pursue the aspects of their lives that they value” and “necessary occupations and care to sustain life and human survival”.

[2] We didn’t know it when we took these decisions but they were aligned with the recommendations of the DevOps movement, as you can see in the following quotes:

“We will actively manage this technical debt by ensuring that we invest at least 20% of all Development and Operations cycles on refactoring, investing in automation work and architecture and non-functional requirements (NFRs, sometimes referred to as the “ilities”), such as maintainability, manageability, scalability, reliability, testability, deployability, and security.” — The DevOps Handbook

[3] The first team we worked with devoted 20% of their time to caring work and 80% to productive work. Other teams that later worked with us distributed the work in different proportions (never less than 20% to caring work).

Note that 20% is the minimum recommended in The DevOps Handbook to keep a healthy system:

The DevOps Handbook authors quote Marty Cagan’s book Inspired: How To Create Products Customers Love.

According to Cagan, “Product management takes 20% of the team’s capacity right off the top and gives this to engineering to spend as they see fit.”

“Cagan notes that when organizations do not pay their “20% tax,” technical debt will increase to the point where an organization inevitably spends all of its cycles paying down technical debt.” — The DevOps Handbook

“By dedicating 20% of our cycles so that Dev and Ops can create lasting countermeasures to the problems we encounter in our daily work, we ensure that technical debt doesn’t impede our ability to quickly and safely develop and operate our services in production.” — The DevOps Handbook

According to Cagan again, “if you’re in really bad shape today, you might need to make this 30% or even more of the resources. However, I get nervous when I find teams that think they can get away with much less than 20%”. This aligns with what we had to propose in some other teams we coached in Lifull Connect.

[4] With the intention of unlocking the system from its initial dynamics, we started by applying several changes to how the team worked. These initial changes were related to the change levers we had identified in the team’s dynamics. Read about them in our previous post about caring work: The value of caring, Manuel Rivero.

[5] At first, we thought we had widened Xavi’s definition of concern. In his talk, he focused mostly on concerns in code as a way to avoid blocking code reviews. Instead, we decided to raise concerns about any inefficiency or waste that we observed in the part of the software value stream comprising development to delivery. Later in a personal conversation with Ricardo Borillo, who was researching how concerns are used in the wild, we discovered that they (Xavi and Ricardo) are using concerns in the same way we are, but Xavi did not manage to transmit this in his talk because of excessively focusing on code reviews.

[6] The talk about Consensus Driven Development is in Spanish.

[7] These ideas are related to Richard Gabriel’s idea of software habitability, and Alexandru Bolboaca’s ideas in his book Usable software Design. We think, both, are in turn, based on Deming’s idea that a system has a huge influence on a person’s performance:

"A Bad System Will Beat a Good Person Every Time." — W. Edwards Deming

[8] At the beginning only Fran Reyes and I worked with Lifull Connect’s Barcelona B2B team. Even though we later got more critical mass when Antonio de la Torre, Manuel Tordesillas and Álvaro García joined the team, by that time the B2B team had already doubled in size, so we still were outnumbered.

[9] We decided to use only three levels of priority following the early three categories of triage in medicine. Some teams decided to use prioritisation models with more categories, but it resulted in a lot of confusion at the time of prioritising. We think it’s better to keep it simple and use only the three categories mentioned: high, medium and low.

[10] We like the poker planning dynamics because it is a quick and simple diverge-and-converge collaboration method that helps reduce information cascades in the team due to power differential and anchoring.

[11] Experiments consisted of researching alternative solutions or tools that we might use to address a concern. We called them experiments to explicitly distinguish them from spikes, so that we avoided the usage of caring work time for spikes which, we think, should be used to reduce uncertainty in features.

[12] They don’t use the term caring work, but they mean the same, “not working on features”.

The DevOps Handbook quotes Marty Cagan arguing about the kind of work that the team might do in that 20%:, “Product management takes 20% of the team’s capacity right off the top and gives this to engineering to spend as they see fit. They might use it to rewrite, re-architect, or refactor problematic parts of the code base… whatever they believe is necessary to avoid ever having to come to the team and say, ‘we need to stop and rewrite [all our code].”

[13] Later this strong boundary was exported to other teams due to similar power dynamics, but this doesn’t mean that this might be necessary in every context. Depending on the culture and people involved the retrospective might be enough.

References

Books

-

Patterns of Software: Tales from the Software Community, Richard P. Gabriel

-

Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit, Mary Poppendieck and Tom Poppendieck

-

The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, and Security in Technology Organizations, Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois and John Willis

-

Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, Nicole Forsgren Velasquez, Jez Humble and Gene Kim

Articles

Talks

Podcasts & Interviews

-

Caring Task con Manuel Rivero, Parte 1, The Big Branch Theory Podcast

-

Caring Task con Manuel Rivero, Parte 2, The Big Branch Theory Podcast

Photo by Karolina Grabowska in Pexels.