Relevant mutants

Published by Manuel Rivero on 22/07/2024

1. Introduction.

Mutation testing gives us information about the fault detection capability of a test suite, whether the assertions that its tests make are good and strong enough to capture regressions.

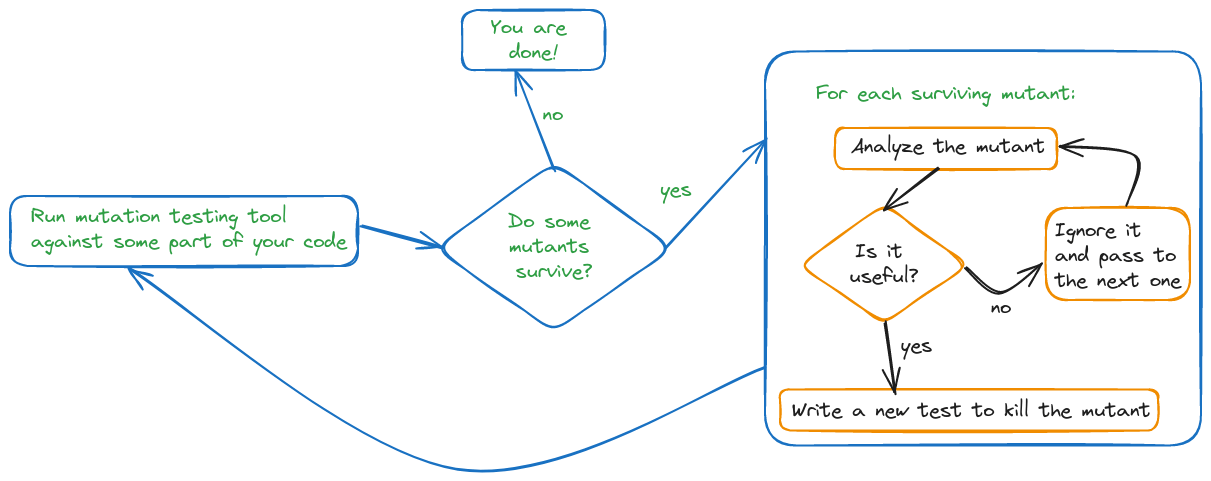

The idea behind it is to purposefully inject a regression in a copy of the code, “the mutant”, run the test suite against this mutant and check if the test suite breaks:

-

If it does, everything is fine, “the mutant is killed”. This means that the test suite protects us from that kind of regression.

-

If it does not, “the mutant survives”. This means that the tests don’t protect us from that regression happening. We may have found something to improve in the tests.

However, when we apply mutation testing to legacy code, not all surviving mutants are a signal of weaknesses in the test suite. Some of the survivors may be related to the existence of dead code, and others may be indicating code that is unnecessary to produce the expected behaviour, and, as such, could be simplified. That is why we must analyse each of the surviving mutants to decide if it is relevant or not, and only if it is so, write new test cases to kill it.

Let’s see it with an example.

2. Analyzing the surviving mutants in the Crazy Portfolio kata.

The Crazy Portfolio kata is a kata to practise working with legacy code that we recently published. This kata is complicated because the code of the Portfolio class, not only has many responsibilities and complex conditional logic, but also, uses dates and time zones, and has side-effects, many boundary conditions between partitions and some implicit invariants[1].

In the code used for this example we had already written characterization tests achieving the maximum possible branch coverage, which is not 100% because there is an unreachable branch in the code, and because of the seams we introduced using Extract and Override Call, which, of course, are not executed in the tests.

Depending on the refactoring we plan to do, it might not be enough to have high branch coverage to start refactoring with confidence, so we applied mutation testing using Stryker and the results were that 36 out of 160 mutants survived.

Apparently, we would need to kill a lot of mutants by adding new test cases in order to improve our test suite, and perhaps some of the mutants might not be so easy to kill.

If we analyse the surviving mutants, we’ll see that there really aren’t that many mutants to kill.

The surviving mutants fall into the following categories:

- Mutants in dead code.

- Mutants in seams.

- Mutants in code not used in the tests because of the seams.

- Mutants in superfluous code that don’t point to weaknesses in the test suite.

- Mutants that do point to weaknesses in the test suite.

2. 1. Mutants in dead code.

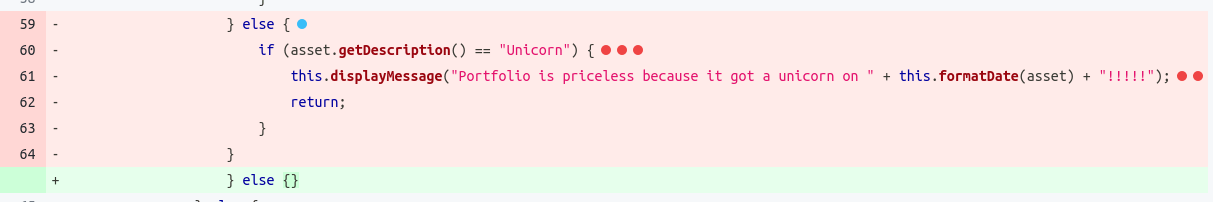

This category includes all the mutations in the non-accessible branch in line 60 that we identified when we wrote the characterization tests.

These surviving mutants are obviously irrelevant.

2. 2. Mutants in seams.

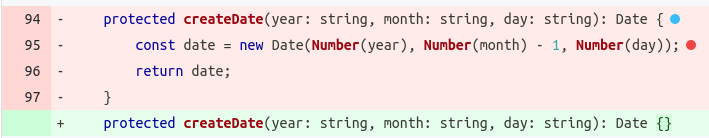

All the mutants in the seams that we introduced, as for instance, the createDate method seen in the following fragment of the Stryker report, are not relevant because the seams’ code is not executed in the tests.

The same happens for the mutants inside the other seams, the protected methods: formatDate, getAssetLines, displayMessage and getNow.

2. 3. Mutants in code not used in the tests because of the seams.

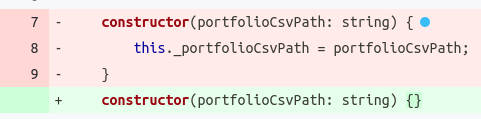

In this group we find the mutation that survives in the constructor of the Portfolio class,

Since we introduced a seam to get the assets without actually reading the file in the unit tests, the portfolioCsvPath field is not used. Therefore this mutant survival is related to the getAssetLines seam that we introduced, and this means that it is not a relevant mutant.

About the categories we have seen so far.

The surviving mutants in the three categories we’ve seen so far can be quickly and safely ignored because they don’t provide any hints on how to improve the test suite or the production code.

We’ll need to examine one by one the rest of the surviving mutants to see if they actually point to weaknesses in our tests or production code that may be simplified. Let’s see the two remaining categories.

2. 4. Mutants in superfluous code that don’t point to weaknesses in the test suite.

Let’s look at the most interesting examples:

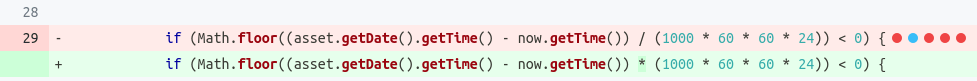

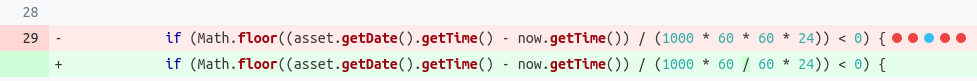

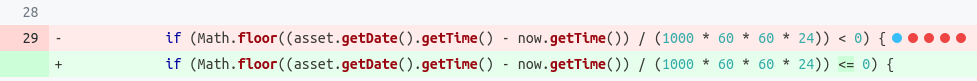

- Case 1: Mutations surviving in line 29.

Have a look at:

or at:

There are several more similar mutations on the same line.

These mutations that replace the division operator with the product operator, and viceversa, seem very confusing and may, at first, be baffling. Why do they survive?

To understand it, we need to look closer at the condition and what it means. The only relevant thing to make the condition true or false is the sign of the difference of the two times in milliseconds: asset.getDate().getTime() - now.getTime(). The rest of the expression, (1000 * 60 * 60 * 24), is just a positive number that is dividing the previously mentioned difference, but it will not change its sign, and therefore, it will not change the evaluation of the boolean expression Math.floor(difference / positive_number) < 0 .

These mutants, that change / operators to * operators, and viceversa, therefore, are not pointing to weaknesses in our tests. What they are indicating, instead, is production code that we don’t need, and, which we could simplify[2], writing the following condition instead: Math.floor(asset.getDate().getTime() - now.getTime()) < 0.

This simplification (that we’d do only once we have stronger tests that eliminate all the relevant mutants) would be enough to eliminate all the related mutants.

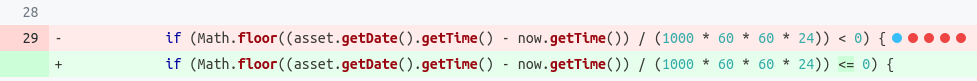

The only surviving mutant in line 29 that is relevant to improve our tests is the one that changes the < operator to the <= operator.

This surviving mutant indicates that our tests are not correctly exercising a boundary condition that exists between two partitions of the values that the difference between the date of the assets and the date the portfolio value is being calculated can take.

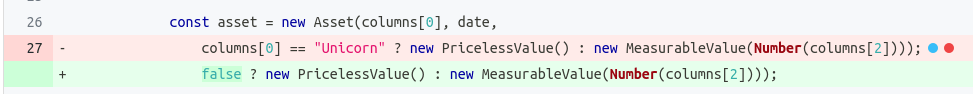

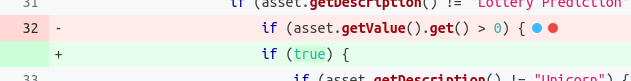

- Case 2. Mutations surviving in line 27.

The survival of those mutations means that the PricelessValue class is not necessary to achieve the behaviour that the tests are protecting. How do they survive?

These mutations survive because the derived PricelessValue class is not used at all in the code. The only thing that is used is the getter of the base object of the hierarchy, MeasurableValue, and therefore the entire inheritance hierarchy is superfluous. The root cause of this problem is the feature envy against the Asset class present in the current code.

Again these mutants are not relevant to improve our tests and we do not have to waste time trying to kill them.

Once we have stronger tests that eliminate all the relevant mutants, we can refactor the code to eliminate the rampant feature envy, and decide if we need to keep the hierarchy or not. These mutants would disappear then.

5. Mutants that do point to weaknesses in the test suite.

We’ve already seen an example in line 29 of a mutant that was indicating that our tests are not correctly exercising a boundary condition. This surviving mutant is changing the < operator to <=.

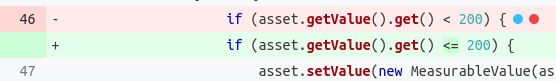

There are other surviving mutants similar to the previous one that also indicate problems testing boundary values, for instance the ones in the lines 32 and 46 presented below:

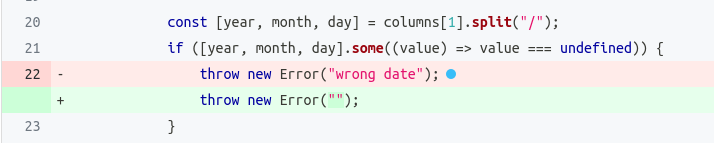

Another example of a surviving mutant that may point to a weakness in our test suite is the one in line 22 showed below:

If we examine the test suite, we’ll see that we are testing that an error is thrown when the date is badly formatted, but we are not checking the error message. In this case, depending on if we want the tests to be coupled with the ”wrong date” string or not, we may decide to kill this mutant or not. We decided to ignore this mutant to avoid coupling the tests to the exception message.

Conclusions.

We’ve shown an example of how not all surviving mutants point to weaknesses in our test suites. Of the original 36 surviving mutants, only 13 of them were relevant to improve our tests suite[3] (we chose to ignore the one related to the error message). Those 13 mutants are related to boundary conditions that are not being properly exercised by the test suite.

Having to kill 13 mutants is a much less daunting task than killing 36 of them. A nice thing is that most of the discarded, not relevant mutants were easy to identify: the ones related to the existence of dead code[4] and to the introduction of seams. This is great because, sometimes, surviving mutants might not be so easy to kill[5].

We also saw another category of surviving mutants that, even though, do not point to improvements in the test suite, are a signal of code that may be unnecessary to achieve the desired behaviour. We may decide to take advantage of these hints in later refactorings once the test suite has improved by killing the relevant mutants.

I hope this detailed example may prove useful to you when you analyse mutation testing results.

Acknowledgements.

I’d like to thank Fran Reyes and Rubén Díaz for revising drafts of this post.

Also thanks to Audiense’s developers for being the beta testers of the Crazy Portfolio kata as part of our deliberated practice sessions. It is always a pleasure to work with you.

Finally, I’d also like to thank Carlos Machado for the photo.

Notes.

[1] We use a simplified version of this kata in our Changing Legacy Code training.

[2] We already talked about surviving mutants pointing to redundant code in a previous post: Mutando para simplificar.

[3] The 13 relevant surviving mutations are in lines 29 (1), 32 (2), 46 (2), 70 (1), 71 (2), 76 (1), 77 (2) and 83 (2).

The surviving mutations in lines 32, 46, 77, and 83 point to boundary conditions which are completely ignored by the test suite (that’s why one of the surviving mutations can completely remove the condition), whereas the surviving mutations in lines 29, 70 and 76 point to partially tested boundary conditions.

[4] We advise using a coverage tool to detect uncovered and dead code before running a mutation testing tool, because coverage tools results are easier to analyze than the mutation testing tools’ ones.

[5] Testing boundary conditions, and, hence, killing mutants related to them becomes much easier if you know about boundaries’ on and off points. These knowledge provides you a systematic way if killing this kind of mutants. We teach these concepts in our revamped TDD training material.