Bundling up to reduce coupling and complexity (peer detection techniques)

Published by Manuel Rivero on 15/02/2026

1. Introduction.

In previous posts[1] we have talked about the importance of distinguishing an object’s peers from its internals in order to write maintainable unit tests, and how the peer-stereotypes help us detect an object’s peers.

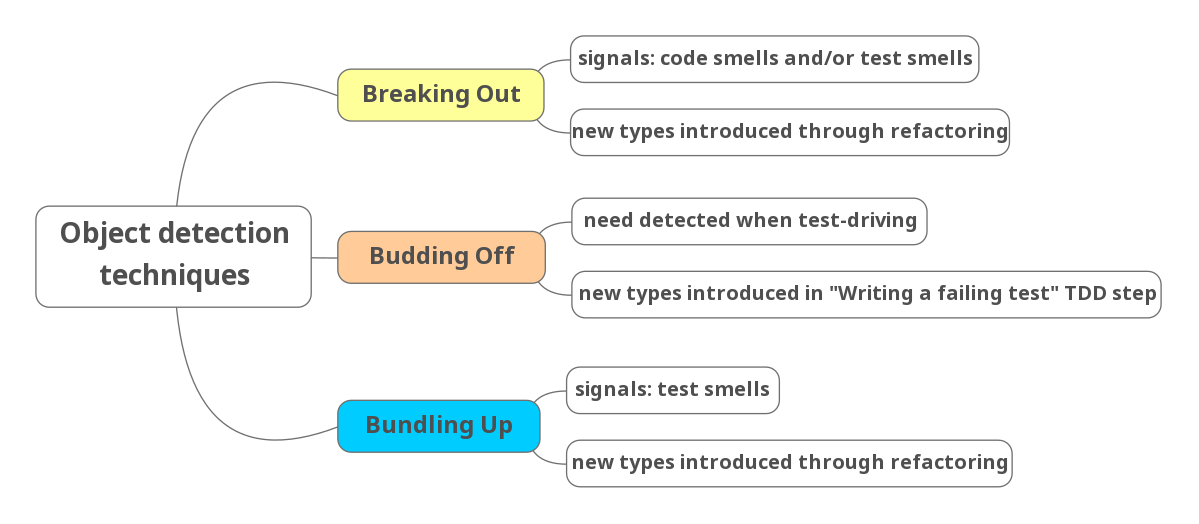

We also presented three techniques, described in the GOOS book, to detect object and value types[2]:

- Breaking out.

- Bundling up.

- Budding off.

and explained in depth one of them: breaking out[3].

In this post we focus on the bundling up technique.

2. Bundling up.

The bundling up technique is an application of the “Composite Simpler Than the Sum of Its Parts” rule of thumb that the GOOS authors describe in chapter 6, Object-Oriented Style.

Note that “composite” refers to “something made of various parts”. In this post, the terms “composite type” and “composite abstraction” refer to a type composed of other types. They should not be confused with the composite design pattern.

The GOOS authors explain that when we compose object or value types to create a composite type, our goal is for the resulting type to exhibit behaviour simpler than that of its components taken together. This means that the composite should reduce complexity rather than merely aggregate it. To achieve this, the composite type’s API should hide its internal components and their interactions, and expose a simpler abstraction to its consumers, (following the Information Hiding principle), which simplifies its consumers.

In short, the “Composite Simpler Than the Sum of Its Parts” rule of thumb states:

“The API of a composite object should not be more complicated than that of any of its components.”

This rule of thumb is useful for evaluating the outcome of a refactoring that was intended to eliminate complexity by introducing a new abstraction.

The bundling up technique can be used to detect both object and value types.

2. 1. Detecting value types.

For value types, bundling up consist in detecting and eliminating existing data clumps through refactoring[5].

2. 2. Detecting object types.

For objects, bundling up consist in hiding related objects into a containing object.

Whenever we observe a cluster of related collaborator objects working together to fulfill a specific responsibility for their consumer, it might be a signal of an implicit concept. We can make this concept explicit by introducing a new composite object type that will package the cluster of related collaborator objects up.

This composite object hides the complexity of the cluster behind an abstraction that allows us to program at a higher level. This not only improves cohesion, but also reduces coupling since consumers only interact with the new composite object.

Furthermore, the new abstraction enhances domain clarity because it more clearly delimits the scope of the cluster of related objects more clearly, and naming it clarifies the underlying concept it represents. At the same time, it shields its consumers from the interactions between the objects in the packaged cluster to fulfill their responsibility.

2. 2. 1. How do we apply a bundling up?

We introduce a new composite object that bundles up some object’s peers through refactoring. The process would be as follows:

-

We create an instance of the new composite object in the constructor of the object for which the related cluster of peers played a specific role, and store that instance in a field. We should inject those peers into the new composite object’s through its constructor when creating its instance.

-

We move the composite behaviour into the new object. We may need to segregate that behaviour first[6].

After this refactoring, the new composite object is an internal of the object from which it was extracted. Consequently, introducing it does not affect the tests, because they are not coupled to it and already cover its behaviour.

2. 2. 2. Signals that a bundling up is necessary.

There are two ways to notice that a bundling up is necessary:

a. Detecting code smells in production code.

We may detect that the object using the cluster of related collaborating objects code suffers from the divergent change code smell which points to a cohesion problem, the class has too many responsibilities.

In chapter 20, of his Working effectively with legacy code book, Michael Feather explains several heuristics to identify responsibilities in a class. Some of them might prove useful to identify clusters of fields and private methods that are being used together to fulfill a responsibility that is not the main responsibility of the class[7]. If most of the fields in the cluster are peers, we have found a candidate cluster for applying a bundling up. Notice that those clusters might be hidden by long methods, so we may need to decompose those first.

b. Detecting testability problems.

These testability problems will appear in the tests of the object for which the related collaborators in the cluster act as peers. We’ll notice that the test setup becomes overly complex because we need to simulate too many peers (and possibly supply additional configuration) just to get the object under test into a relevant state. The authors of the GOOS book illustrate this situation when describing the “Bloated Constructor” test smell in chapter 20 of the book, which is devoted to test smells that may indicate design problems[8].

The tests might be especially painful to maintain, if there’s still some churn[9] in the interfaces of the peers, or in their interactions to fulfill their composite responsibility because the tests are coupled with them and that churn will affect them.

Take in mind that this signal might take longer to be noticeable than detecting code smells in the production code, but when it appears it points to a stronger need to to bundle up some of the object’s peers.

If we are suffering testability problems, extracting a new internal composite object won’t be enough, we’ll also need to promote the new composite object to be a peer and refactor the tests.

2. 2. 3. Refactoring the tests.

We promote the internal composite object to be a peer of the object that uses it by introducing an interface for the role it plays, then invert the dependency on it, and inject it through the constructor of the object that uses it.

Then we refactor the tests, to simplify them:

-

We test the new composite object directly.

-

We use test doubles to simulate the behaviour of the composite in the tests of the code from which it was extracted.

In the case of a bundling up, promoting the internal composite object to be a peer won’t reduce the structure-insensitivity of the tests, as was the case for a breaking out. This happens because a bundling up reduces the overall coupling.

Imagine that we have an object that has 5 peers, 3 of which form a cluster that work together to fulfill some responsibility for the object. If we bundle up the cluster in a new composite object and make it a peer, the object will now have 3 peers (2 original peers that were not part of the cluster + the new composite object) instead of the original 5. This means that when there are testability problems making the new composite object a peer makes sense because it increases the structure-insensitivity of the tests[10].

Furthermore, the tests using the interface of the composite object directly will be more focused which will improve the overall tests’ readability, writability, specificity and composability.

The tests of the client of the new abstraction will also be more maintainable because the new abstraction shields its consumers from any churn inside it, i. e., changes in the interfaces or interactions between the peers the abstraction is bundling up. This is one of the advantages of information hiding. We benefit even more from this protection while the functionality within the cluster is still actively evolving.

As in the case of breaking out, we prefer to promote the new internal composite object to peer only if we are experiencing testability problems. Otherwise, we keep it as an internal to avoid coupling tests to an abstraction that might prove unnecessary, in case coupling to it ends up providing no benefits.

3. An example.

Some time ago, we were developing an application that processed clicks on ads in different portals and associated them to the campaign they should be charged to using several criteria.

3. 1. Before applying a bundling up.

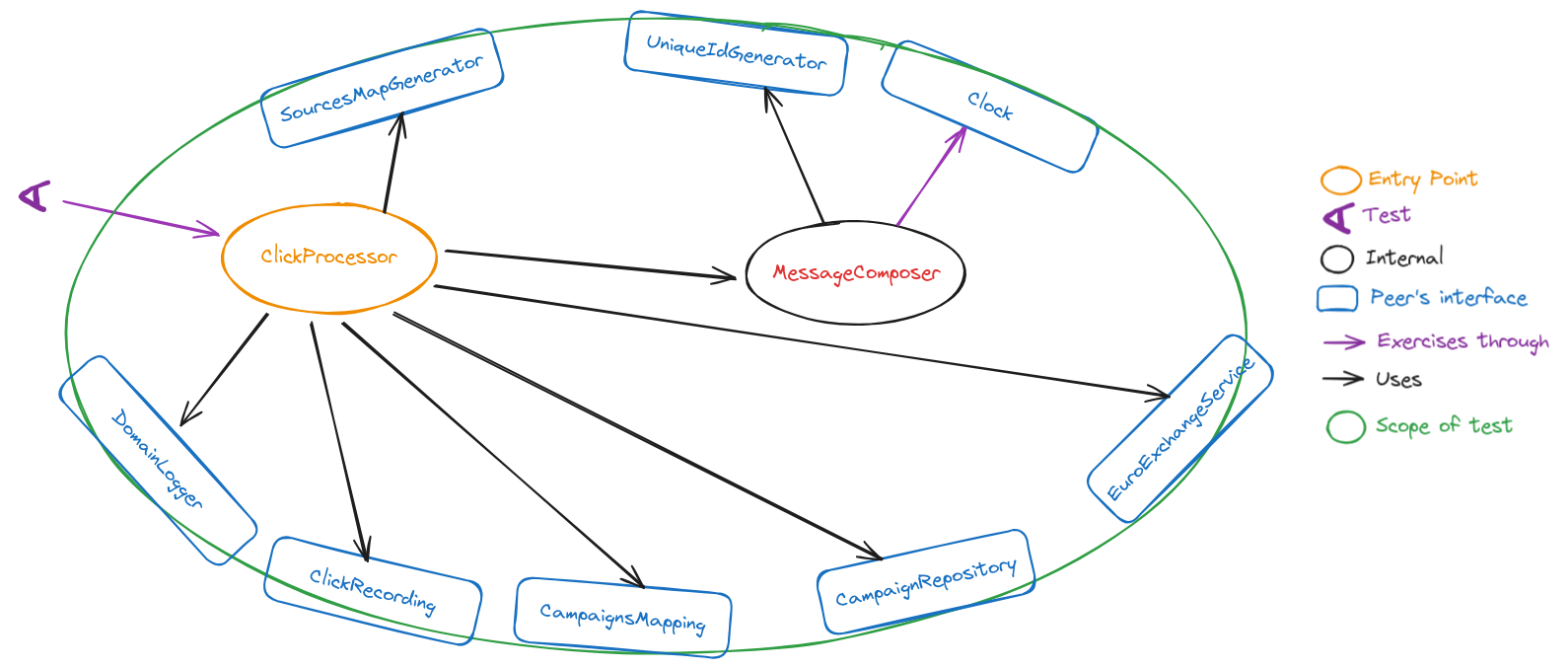

Early in the development of the application we had a design like the one shown the following diagram:

The ClickProcessor class had 7 collaborators, of which 6 were peers[11] (SourcesMapGenerator, DomainLogger, ClickRecording, CampaignsMapping, CampaignsRepository and EuroExchangeService), and 1 was an internal, (MessageComposer), that in turn had two peers (Clock and UniqueIdGenerator).

The 6 peers of ClickProcessor and the 2 peers of MessageComposer matched the dependency role stereotype. They were ports of the application.

This meant that the unit tests of ClickProcessor had to use 8 test doubles to simulate the behaviour of the 8 dependencies.

Since the application was still in flux as we iterated to add new sources of campaigns and ads, the logic in ClickProcessor was evolving rapidly and soon we would need to add new peers to retrieve information from new sources. This churn transmitted to the tests that had to keep up with the changes in logic and peers. The complicated set up of the tests and that churn were causing us a lot of pain.

As their names indicate, two of the peers of ClickProcessor were related to campaigns: CampaignsMapping and CampaignsRepository.

We also observed that most of the churn in ClickProcessor was coming from iterations to evolve the logic to retrieve the campaign to which a given click was assigned. Furthermore, we also knew that this campaign retrieval logic was soon to grow to support new sources for campaigns and ads coming from two recently acquired companies.

There were three peers working together to retrieve the campaign to which an ad was assigned: CampaignsMapping, CampaignsRepository and EuroExchangeService. We decided to bundle up this cluster to shield ourselves from churn in the campaign retrieval logic, reduce coupling and improve test maintainability. Consequently, we extracted a new composite object, CampaignRetrieval which encapsulated the cluster and was responsible for retrieving the campaign.

3. 2. After introducing the new composite type.

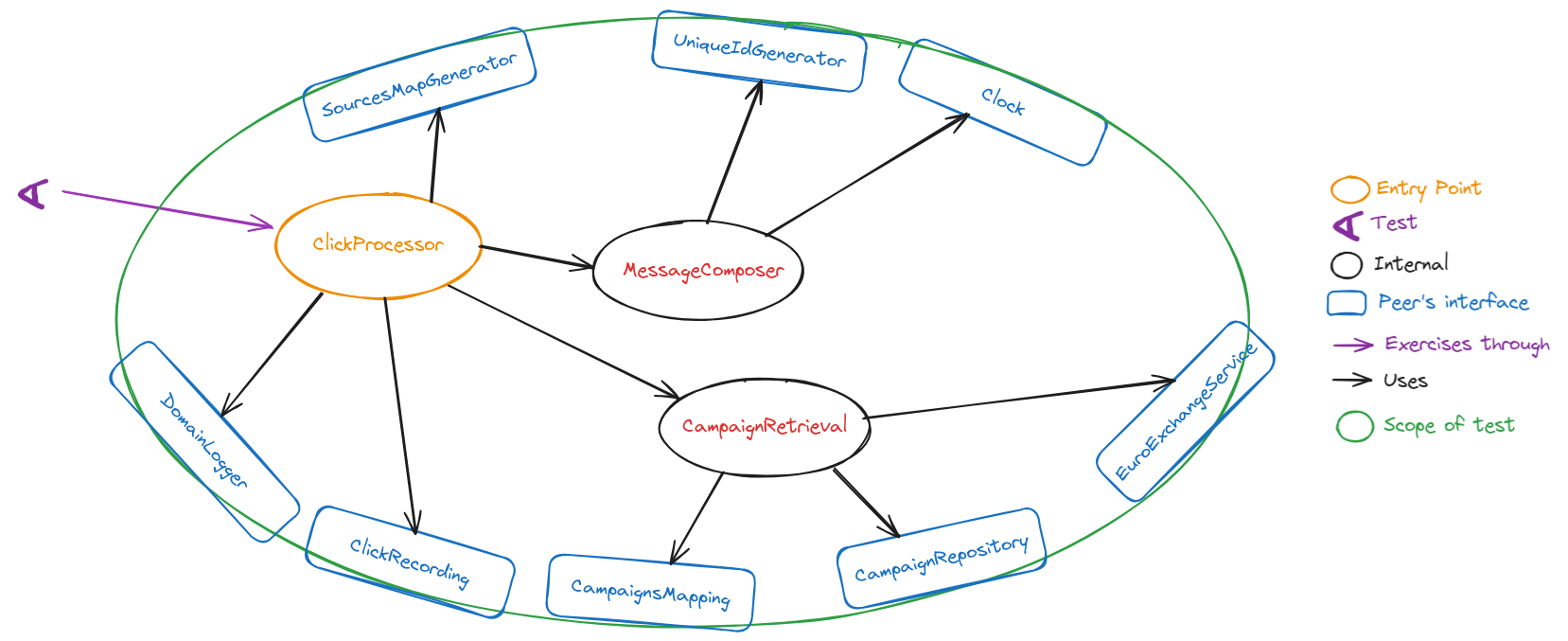

The new composite type, CampaignRetrieval, was an internal of ClickProcessor. The resulting design is shown in the following diagram:

ClickProcessor had 5 collaborators, of which 3 were peers, SourcesMapGenerator, DomainLogger and ClickRecording; and 2 were internals:

-

MessageComposerwhich in turn had 2 peersClockandUniqueIdGenerator; and -

CampaignRetrievalwhich in turn had 3 peers alsoCampaignsMapping,CampaignsRepositoryandEuroExchangeService.

This refactoring reduced the overall coupling because ClickProcessor went from having 7 collaborators to having 5. As we explained in a previous section, the coupling reduction is equal to the number of peers bundled in the new composite object minus one, in this case, 3 – 1 = 2.

Since, CampaignRetrieval was still an internal of ClickProcessor, the tests didn’t change after this refactoring.

3. 3. After promoting the new composite type to be a peer.

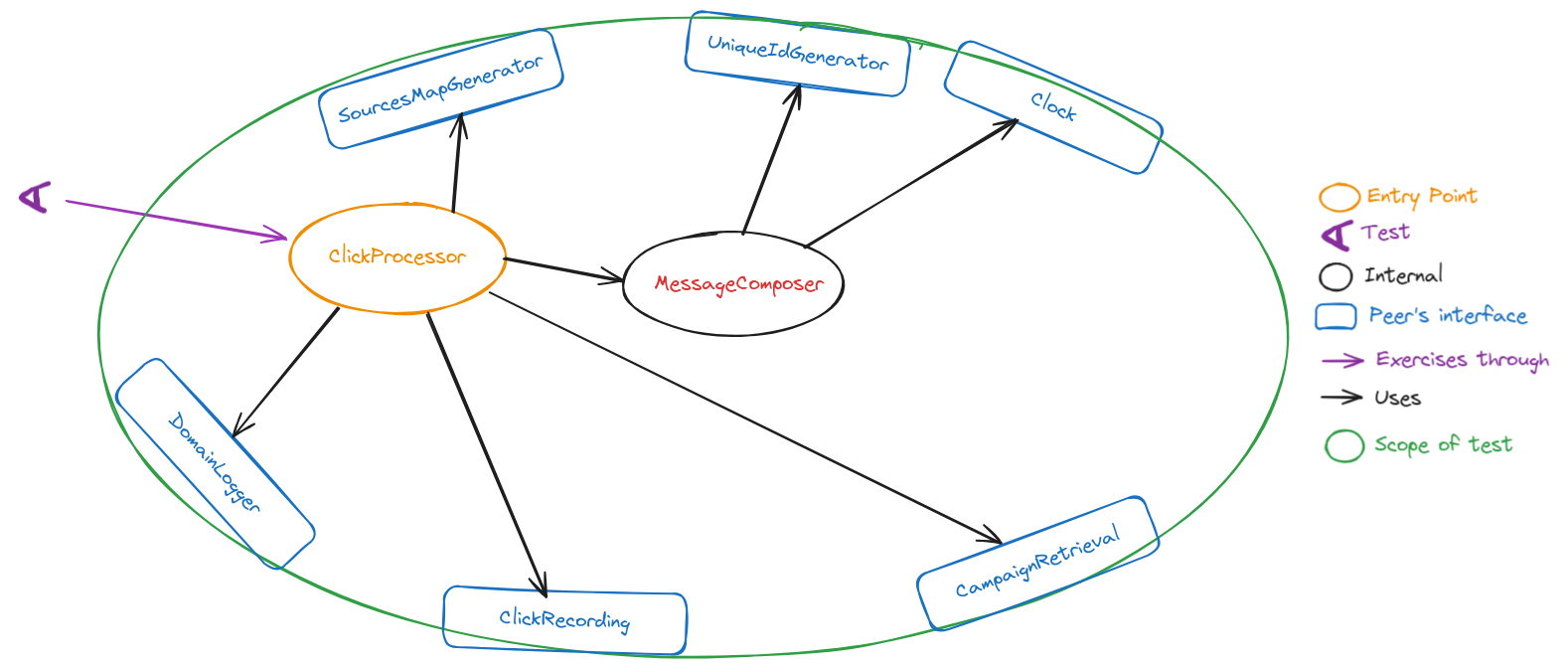

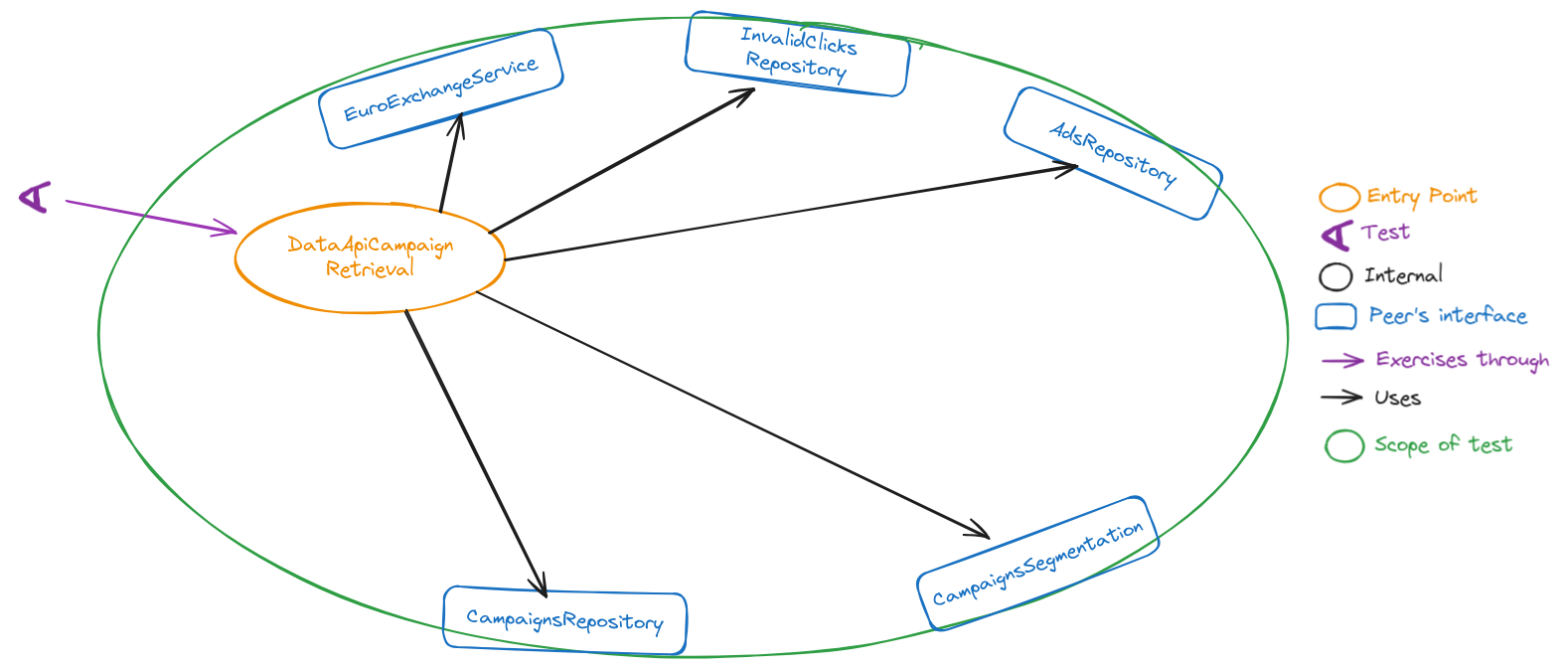

Finally, we promoted CampaignRetrieval to be a peer and simplified the tests (the details of this refactoring in section 2. 2. 3. Refactoring the tests). The resulting design is shown in the following diagram:

After this final refactoring, the ClickProcessor class still had 5 collaborators, but now 4 of them were peers (SourcesMapGenerator, DomainLogger, ClickRecording and CampaignRetrieval), and only 1 was an internal, MessageComposer which in turn had 2 peers: Clock and UniqueIdGenerator.

The tests of ClickProcessor became much simpler: they were coupled to 6 peers instead of the 8 before the refactoring and therefore required only 6 test doubles. This reduction in coupling was reflected in the tests, which became more focused and were shielded from the churn in the campaign retrieval logic.

The campaign retrieval logic resided in the class implementing the CampaignRetrieval interface, NotYetUsingDataApiCampaignRetrieval, (a temporary name reflecting that we were still iterating its behavior). Its focused tests were the only ones affected by ongoing changes in the campaign retrieval code.

Reducing the number of peers of ClickProcessor by 2 may not seem much, but shielding its tests from the churn in the campaign retrieval logic made a big difference for us, because it removed the high maintenance burden of having to update them every time a small change happened in the campaign retrieval code.

Eventually the logic to retrieve a campaign grew in complexity until it became a subsystem in its own right, thus having applied a bundling up to that initial cluster of 3 objects proved to be a very successful bet[12].

This table summarizes the reduction in complexity on this stage of the process.

| Stage | ClickProcessor | ClickProcessor test | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before bundling up | 1 internal (2 peers) + 6 peers, 8 peers in total | 8 test doubles | Many peers, high coupling to tests |

| After introducing composite | 1 internal (2 peers) + 1 internal (3 peers) + 3 peers, 8 peers in total | 8 test doubles | Better cohesion, same coupling to tests |

| After promoting composite to peer | 1 internal (with 2 peers) + 4 peers, 8 peers in total | 6 test doubles | Same cohesion as previous stage, reduced coupling to tests: improved testability |

4. Conclusions.

The bundling up technique is a refactoring that manages and reduces complexity by grouping related collaborators into a single composite object. It is an application of the “Composite Simpler Than the Sum of Its Parts” rule of thumb. Rather than merely aggregating objects, the goal of bundling up is to create a higher-level abstraction that makes the design simpler to understand, reason about, and use.

This technique can be applied to both value and object types. In the case of values, bundling up involves detecting and eliminating data clumps by introducing meaningful abstractions that represent them explicitly. For objects, it consists of identifying clusters of collaborators that work together to fulfill a specific responsibility and packaging them inside a new composite object. By doing so, implicit concepts are turned into explicit abstractions with clear boundaries and well-defined responsibilities.

Applying bundling up brings several important design benefits. It improves cohesion by isolating a distinct responsibility within its own abstraction, and it reduces coupling because clients interact with one composite object instead of many individual objects. It also improves domain clarity, since naming the new abstraction helps reveal the underlying concept it represents. At the same time, it strengthens information hiding by shielding consumers from internal interactions and future changes within the packaged cluster of objects.

In the case of object types, there are signals that indicate when bundling up may be necessary. In production code, code smells such as divergent change, long methods, or large classes often point to hidden clusters of related behaviour. In tests, the need for bundling up becomes apparent when setup logic grows complicated requiring many test doubles, or when tests become fragile because they are tightly coupled to a cluster of collaborating objects in churn. These testability problems are strong indicators that an implicit abstraction should be made explicit.

The refactoring process typically involves introducing a new composite object, injecting the relevant peers into it, and moving the related behavior into this new abstraction. Initially, the composite can remain an internal of the original object, leaving existing tests unchanged. If testability problems persist, the composite can then be promoted to an explicit peer, which usually simplifies tests by reducing the number of awkward collaborators they must simulate. Unlike breaking out, bundling up tends to increase the structure-insensitivity of the tests because it reduces coupling.

In summary, bundling up is an effective way to uncover meaningful abstractions, control complexity, and improve maintainability in both code and tests. Even small reductions in coupling can have a significant impact when they shield consumers from volatile parts of the system. As shown in the example, a well-chosen composite may naturally evolve into a subsystem, confirming the value of bundling up as a long-term investment to create a more sustainable design.

Our next post in this series will focus on the budding off technique.

Thanks for reading to the end of this post. We hope the ideas presented here prove useful in your own work.

The TDD, test doubles and object-oriented design series.

This post is part of a series about TDD, test doubles and object-oriented design:

-

The class is not the unit in the London school style of TDD.

-

“Isolated” test means something very different to different people!.

-

Heuristics to determine unit boundaries: object peer stereotypes, detecting effects and FIRS-ness.

-

Breaking out to improve cohesion (peer detection techniques).

-

Refactoring the tests after a “Breaking Out” (peer detection techniques).

-

Bundling up to reduce coupling and complexity (peer detection techniques).

Acknowledgements.

I’d like to thank Emmanuel Valverde Ramos, Marabesi Matheus and Fran Reyes for giving me feedback about several drafts of this post.

Finally, I’d also like to thank Cottonbro Studio for the photo.

References.

-

Growing Object Oriented Software, Guided by Tests, Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce.

-

Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts, Anne Duke

-

Mock roles, not objects, Steve Freeman, Nat Pryce, Tim Mackinnon and Joe Walnes.

-

Mock Roles Not Object States talk, Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce.

-

Object Collaboration Stereotypes, Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce.

-

The class is not the unit in the London school style of TDD, Manuel Rivero

-

“Isolated” test means something very different to different people!, Manuel Rivero

-

Heuristics to determine unit boundaries: object peer stereotypes, detecting effects and FIRS-ness, Manuel Rivero

-

Breaking out to improve cohesion (peer detection techniques), Manuel Rivero

-

Refactoring the tests after a “Breaking Out” (peer detection techniques), Manuel Rivero

Notes.

[1] These are the posts mentioned in the introduction:

-

The class is not the unit in the London school style of TDD in which we commented, among other things, the importance of distinguishing an object’s peers from its internals in order to write maintainable unit tests.

-

Heuristics to determine unit boundaries: object peer stereotypes, detecting effects and FIRS-ness in which we explained how the peer stereotypes helped us identify an object’s peers.

[2] When we use the term object in this post, we are using the meaning from Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests (GOOS) book:

Objects “have an identity, might change state over time, and model computational processes”. They should be distinguished from values which “model unchanging quantities or measurements” (value objects). An object can be an internal or a peer of another object.

[3] We devoted two posts to explain the breaking out technique in depth:

- Breaking out to improve cohesion (peer detection techniques), and its continuation,

- Refactoring the tests after a “Breaking out” (peer detection techniques).

[4] This mind map comes from a talk which was part of the Mentoring Program in Technical Practices we taught in 2024 in AIDA.

[5] In the Value Types section of chapter 7, Achieving Object-Oriented Design of GOOS, the author explains that they apply a bundling up when they detect an instance of the data clump code smell: “when we notice that a group of values are always used together, we take that as a suggestion that there’s a missing construct”.

They continue detailing how they refactor it: “A first step might be to create a new type with fixed public fields—just giving the group a name highlights the missing concept. Later we can migrate behaviour to the new type, which might eventually allow us to hide its fields behind a clean interface.”

[6] Applying Extract Function/Method and other related refactorings, see chapter 6, A First Set of Refactorings, of Martin Fowler’s Refactoring book.

[7] We think that the following four heuristics to detect responsibilities may be useful to detect clusters collaborating peers and methods: Grouping Methods, Looking at Hidden Methods, Decisions that may change and Internal Relationships.

[8] You can also find posts explaining these test smells in their old blog under the category: Listening to the tests .

[9] In the context of software development, churn refers to frequent changes in the code, interfaces, or design.

Specifically, in this post, we are talking about:

-

“Churn in the interfaces”: Meaning that the definitions of how different components (peers) communicate are changing often (e.g., method names, parameters, or return types are being modified repeatedly).

-

“Churn in their interactions”: Referring to frequent changes in how these components collaborate or the sequence of steps they take to achieve a goal.

[10] If a cluster contains n peers of an object that work together, bundling them into a composite object and making it a peer of the original object will reduce the number of peers the object is coupled with by n – 1 (we remove the n peers in the cluster, but add one new peer: the composite object).

[11] You can find several practical heuristics that help you decide whether a collaborator should be considered a peer or an internal in the post: Heuristics to determine unit boundaries: object peer stereotypes, detecting effects and FIRS-ness.

[12] When I left the application the implementation of CampaignRetrieval already had 5 peers and several internals.